Hello, this is Takashi Matsunaga.

At I.CEBERG, I explore collage-based expressions, while at WOW I work as a director and motion designer. On the side, I’ve continued an independent creative group called “Tsuribu Tokyo” since my student days, and in recent years, I’ve also been a part-time lecturer at Musashino Art University.

We’re launching a new series called I.CEBERG TALK, built around the theme of “having conversations with people I want to talk to at that moment.”

Our first guest is Koji Aramaki, the founder and director of the motion graphics studio SIGNIF.

Although I’ve been following Aramaki’s work for a while, this was actually our first proper conversation. We talked freely—moving back and forth between our roots and creative backgrounds—exploring both our similarities and differences.

You can listen to the full episode on Spotify.

Part 1

Part 2

Here, we’d like to share a short excerpt from the conversation.

This time, we visited the SIGNIF office for the interview.

“Individual Roots and Shared Paths”

Matsunaga:

I’ve always been intrigued by your work, Aramaki-san — though this might sound a little awkward to say.

Aramaki:

Not at all, please go ahead.

Matsunaga:

Your work isn’t too clean — it prioritizes edge and texture over perfect deliverables. Like, I sometimes think, “This would totally fall apart under heavy compression” (laughs). But that’s exactly what I love about it. In the motion design world, there are all these “correct” workflows — preserving grading information, keeping everything tidy and optimized. But your work doesn’t seem confined by that. You go beyond. Is this okay to say? (laughs)

Aramaki:

Absolutely (laughs). You’re actually putting it quite gently.

Matsunaga:

I guess I’ve always been drawn to that kind of deconstruction — ignoring conventions for the sake of what feels good or interesting. That sense of friction or imbalance really caught my attention.

Aramaki:

Yeah, I wouldn’t say it’s entirely conscious, but I think it’s similar to what you’re describing. Things like formats and rule systems — they just exist, but breaking them isn’t necessarily wrong. If you follow every rule perfectly, it can get pretty dull. So when I’m in a position to bring my own tone or do what I want, I try to treat “whether to follow the rule or not” itself as a creative choice.

Matsunaga:

So you understand the conventions, but you’re okay with not always obeying them.

Aramaki:

Exactly. If you stick too closely to a format, those internal constraints just grow stronger and stronger, and that’s suffocating. So sometimes I think, it’s better to act a little foolish on purpose. Like, “Yeah, this will definitely collapse once it’s compressed — bitrate-wise, this is impossible — but whatever, it gets the point across” (laughs).

Matsunaga:

That’s the kind of “otherness” I sense in your work. I use that word — “otherness” — to describe it. Personally, I don’t really see myself as a motion graphics artist, or even part of the “video production” scene per se. But when I look around, your work stands out. It just feels different — and that difference is so important.

Aramaki:

Right. You originally started as a graphic designer, didn’t you?

Matsunaga:

Yeah. After graduating from university, I joined a production company mainly focused on graphic design for advertising — posters, printed materials, that kind of thing. Back then, Illustrator was my main tool. Later, when I tried Cinema 4D, I thought, “Oh, this is like Illustrator with depth and time added — that’s actually great,” and that led me into CG.

Aramaki:

Back when I was a student, Vimeo had a huge influence on me. There was this unspoken game of how cleverly you could twist moving images — that kind of visual wit was a big part of what made motion graphics exciting. For example, creators like TAKCOM were making entire pieces just using ambient occlusion, which was such an unconventional approach. Challenging those “you normally wouldn’t do that” ideas — that’s what I found fascinating about motion graphics, and I think that sense of playfulness still stays with me today.

Matsunaga:

Yeah, I also love that kind of clever minimalism — figuring out how to add wit with the fewest elements possible. When you take CG too seriously, it tends to get heavy, so I was always interested in how to make things lighter but still a bit offbeat or strange. That kind of playfulness really appeals to me too.

Aramaki:

Did you watch Vimeo back then, Matsunaga-san?

Matsunaga:

Not much, actually. I barely watched Vimeo when I was a student. I wanted to talk about our roots today — and if I remember right, you submitted work to the Student CG Contest back then, didn’t you?

Aramaki:

I did.

Matsunaga:

Actually, Tsuribu also started with the Student CG Contest. Back then it wasn’t about motion design at all — we were making these kind of DIY, home-center style videos, like physically cutting wood and building sets for live-action shoots. The contest has since changed its name to NYAA, but at the time, it was pretty much the only “anything goes” kind of arena — like a creative Tenkaichi Budokai (the ultimate open tournament).

Aramaki:

Yeah, same here. That’s where I first met people like Fumi Ohashi, Wataru Uekusa, and Ryo Hirano.

Matsunaga:

Back then, the Student CG Contest really accepted anything—films, installations, whatever. Everything was put side by side, and the strongest piece won. I admired that spirit. The works I submitted were like comedic short films, sort of skit-style pieces with a touch of surreal humor. They had stories, but also focused on the weirdness of the visual expression—like taking an OK Go–style approach and seeing how far I could push it.

Aramaki:

Oh right, the one with that unusual title? I actually watched it again yesterday (laughs).

Matsunaga:

(laughs) So embarrassing. But yeah, I was experimenting with all sorts of things under that “try everything” mindset. After graduation, I was kind of lost—like, what am I supposed to aim for now? There wasn’t really another open arena like that contest except maybe the Japan Media Arts Festival. Everything else was too segmented. If it was film, you had to go through something like PFF (Pia Film Festival), which is a whole different scene. I didn’t know where my kind of work belonged. I tried making short films that incorporated VFX elements, but filmmaking turned out to be really hard—maybe because I’d seen too many good ones. Making something people can genuinely sit through is tough. And having people act adds a whole new level of complexity.

Aramaki:

Yeah, that’s really hard.

Matsunaga:

So I stopped making films for a while. Around that time, I started getting small offers for music videos, so I worked on those here and there. I can’t say I ever felt this is it with music videos, but I did like how you could clearly say, “This is finished.”

Aramaki:

I totally get that. Even if there are “errors,” they’re often accepted as part of the piece.

Matsunaga:

Exactly. It’s easier to say, “That’s just the world of this work.” It’s a forgiving format. That led to projects like the interview video I did with Hakushi Hasegawa — it had a rough timeline like a narrative, but it was also about visual expression. That combination worked out pretty well. From the start, I’d always wanted to merge film-like storytelling with visual experimentation, and I feel like that’s finally taking shape recently. Even in my recent exhibition Who_Is_Pokopea?_, there was kind of a timeline to the installation — an intro in the caption, an unfolding narrative, and a set of physical objects within a world. Exhibitions have that kind of structure, and I found that really fun.

Aramaki:

I see. For me, I got into video after joining a film circle at university. At first, I was making short films too.

Matsunaga:

That one with the girl?

Aramaki:

Yeah, that one — that’s probably one of the few that actually worked (laughs). But honestly, the circle I joined wasn’t really serious about filmmaking. It was more like, during orientation week, they’d feed you dinner every night — so I just started hanging around. Then I found out they had these semiannual screening events, so I made short films for those. But I always thought, “Man, this is kind of painful to watch” (laughs). Most of the members weren’t there because they wanted to act or make films.

Matsunaga:

Yeah, that makes sense. Filming people’s performances is really hard (laughs).

Aramaki:

Totally (laughs). Watching my own videos with people acting, I’d think, “This is rough…” Around that time, Vimeo and other video platforms started emerging, and I discovered motion graphics there. I thought, “Wait, this doesn’t involve people — maybe I can actually do this.” (laughs) The idea that I could make everything by myself was huge, and that’s how I started creating motion graphics. Later, I made a live-action/motion graphics hybrid piece with a team and submitted it to the Student CG Contest. I also started uploading solo motion works to Vimeo, and over time that turned into professional work.

Matsunaga:

So in a sense, you hit a wall — not a failure exactly, but you realized, “This path might be risky.”

Aramaki:

Yeah, exactly (laughs). And to be honest, I studied sociology at Tokyo Metropolitan University, so there was literally no one around me doing motion graphics.

Matsunaga:

I want to hear more about that. The film circle was in Tokyo Metropolitan University?

Aramaki:

Yeah, it was a campus circle called the “Broadcast Research Club.” The official premise was that we “researched broadcasting,” but in practice we just made videos. Other universities had similar clubs that did things like radio dramas, so we’d visit each other’s presentations sometimes. To be blunt, a lot of it was by wannabe voice actors doing radio plays — and I’d be sitting there like, “Wow, this is... something.” (laughs) But it was super chill, which was kind of nice.

Matsunaga:

Were there lots of people into anime or subculture?

Aramaki:

The senior who influenced me was that type, but most members were just regular college students — listened to whatever music was popular at the time. Back then, anime wasn’t nearly as mainstream, so hardly anyone was into it. At our screening events, someone would literally show footage of them playing Winning Eleven (laughs).

Matsunaga:

So it wasn’t like a culture-deep-diving kind of community.

Aramaki:

Yeah, let’s just say the cultural capital there wasn’t particularly high (laughs). But there were a few interesting people. Around that time, the university had just launched a new program called Industrial Art Course — I think it started the year before I enrolled. The first batch of students in any new program tends to be a bit eccentric, right?

Matsunaga:

Yeah, first-year cohorts are always like the Downtown of their generation (laughs).

Aramaki:

Exactly (laughs). A few people from that course joined the circle too. Our current producer is actually one of its graduates. I was really inspired by those people. Before that, in junior high and high school, I was just a totally normal countryside kid — I had almost zero exposure to design or video. I listened to bands like BUMP OF CHICKEN and ELLEGARDEN — just what was popular at the time.

SIGNIF recently moved its office to Senzoku. Aramaki says he likes the relaxed atmosphere of the neighborhood — it strikes just the right balance.

Miyadai Shinji and The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya

Matsunaga:

Speaking of that, when did you first watch Eureka Seven or Evangelion?

Aramaki:

The one anime that really stuck with me from high school was Mononoke, which aired on Fuji TV’s Noitamina block. But aside from that, I honestly didn’t watch much anime back then. The department I was in at university was called the “Faculty of Urban Liberal Arts,” which was kind of a catch-all for humanities — you could branch into sociology, psychology, and so on. In our first year, there was this introductory lecture for each course, and the professor in charge of sociology happened to be Shinji Miyadai.

And in his very first lecture, the thing he played was The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya.

Matsunaga:

(laughs) Seriously? That’s how it started?

Aramaki:

Yeah. He was like, “This is the cutting edge of sekai-kei, so I’m sure you all get it, right?” That was the vibe. But at that point, I hadn’t really watched anime at all, so I thought, Wait — do I need to watch anime to study sociology? (laughs)

Matsunaga:

So you felt like you had to know subculture just to keep up.

Aramaki:

Exactly. Back then, I wasn’t really exposed to culture in general, so I didn’t even understand what “subculture” really meant. I just thought, Guess I should start watching anime then. It was around the time Nico Nico Douga and other video platforms were taking off, and visual content was exploding. Consuming all that was genuinely fun — I’d go to Tsutaya and rent a bunch of DVDs, trying to catch up. It felt like, If I’m studying sociology, I need to understand culture, and that’s what pushed me to really dive into anime.

Matsunaga:

That’s fascinating — what a unique route into it.

Aramaki:

Yeah, for sure. I think I was pretty late to most of the famous series. I binge-watched everything around that period — Evangelion, Ghost in the Shell, Eureka Seven, all at once. It was also the era when sakuga MADs were popping up on Nico Nico Douga, and watching those made me realize how fascinating animation could be. I just got completely hooked.

Matsunaga:

Right, there were tons of sakuga MADs back then — I used to watch those too. Especially ones featuring animators from Production I.G or the Gainax legends. I’d know specific sequences without even having seen the original shows (laughs).

Aramaki:

Yeah, at some point I felt like I should actually watch the full shows, not just the MADs. So I’d rent DVDs of the ones that impressed me most and go through them properly. I’m not sure how much of that experience directly translates into what I do now, but when I watched those sakuga MADs, I was struck by how dynamic and exaggerated the movement was — that sense of kerenmi (flamboyant bravado). I remember thinking, Maybe there’s a way to bring some of that energy into motion graphics.

Back then, Japan had platforms like Nico Nico Douga for subculture, but the motion graphics community really only existed on Vimeo — and also sites like Stash, but that was still pretty limited. Most of the work being shared in motion graphics was from overseas. So while I was trying to figure out how to differentiate myself, anime became a huge influence.

Matsunaga:

Funny coincidence — I was at Musashino Art University yesterday. There’s a full-time professor there named Yamazaki, who actually invited me to start teaching part-time. I told him, “Tomorrow I’ll be talking with Aramaki-san from SIGNIF,” and he was like, “Oh, nice!” Then I said, “Did you know he was in Shinji Miyadai’s seminar?” and he just went, “What!? Wait— is that information out there somewhere!?” (laughs)

Aramaki:

Yeah, I don’t think I’ve ever really talked about that in any official interview or anything. To be honest, I felt pretty isolated in the beginning — I didn’t have peers from the same background. Everyone around me was from Musabi or Tama Art University, and I remember thinking, man, that must be nice.

Matsunaga:

Do you think that background gave you any sort of advantage — consciously, I mean?

Aramaki:

Honestly, I always thought of it as a disadvantage (laughs). But if there’s one part of it that turned into an advantage, it’s that I’ve always felt like an outsider. So, like we talked about earlier — when it comes to industry standards or “proper” ways of doing things, I can kind of say to myself, well, I’m on the outside anyway, so I don’t have to fully conform.

And as for how I think about video, I don’t really know how structured art school education is, but since I basically taught myself everything, I ended up constantly questioning the premises. I think that comes partly from sociology. Miyadai used to say that “sociology is a discipline that traces assumptions back to their roots.” Like, society has certain rules — but what are those rules based on, and why do they exist? Analyzing that structure is the interesting part of sociology, he said.

So I started to see film and video formats in a similar way — not as fixed frameworks, but as things that only appear to exist as standards, and can actually be changed. I think that mindset — this sense that nothing is absolute, that everything can be redefined — might be one of the few advantages, or at least one of the factors that helps me create work that feels different from people who came up through the more traditional film or art-school routes.

Aramaki at his desk. (I asked—well, insisted—that he sit down for a quick photo.)

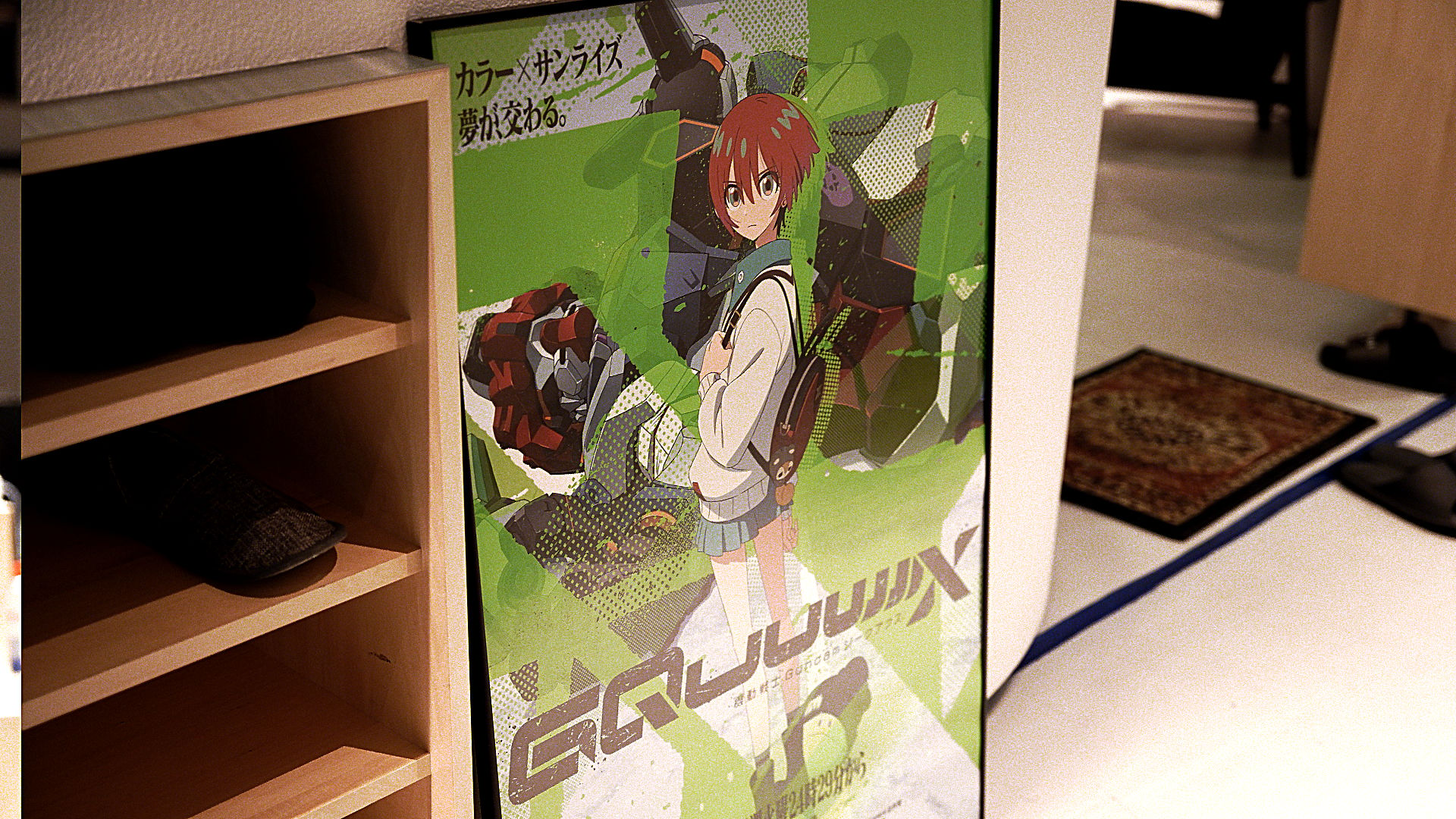

Most recently, he participated as a motion graphics artist in Mobile Suit Gundam GQuuuuuuX.

“Position and Survival Strategy”

Matsunaga:

One of the questions you wrote beforehand was, “Do you think about your own position — and does that awareness affect what you create?” When I saw that right at the top, I kind of laughed because it was so dead-on. What made you want to bring that up?

Aramaki:

Recently I was talking with some of the members at SIGNIF, and I realized — not many people actually think consciously about where they stand in the bigger picture. Like, not many creators seem to imagine how their work is perceived from the outside — how it’s evaluated, and how they want to position themselves in relation to that perception. It made me wonder if that sort of meta-awareness is rare.

And I thought you, Matsunaga-san, probably think about it a lot — like your relationship with WOW’s legacy, for instance. I was curious whether that awareness shapes your approach.

Matsunaga:

Yeah, my whole creative life is basically structured around survival strategies. I’ve always been playing that relative positioning game.

Aramaki:

I thought so (laughs). I kind of feel the same way myself.

Matsunaga:

But at the same time, I’m not always sure if that’s the right way to live (laughs).

Aramaki:

You mean, not knowing if your strategy for survival is actually a good one?

Matsunaga:

Right. I think both paths — doing what you’re good at, and doing what you love even if you’re not good at it — are equally meaningful. But personally, I’m not the type who can keep doing something I love but suck at. I immediately get this alarm in my head saying, “This way lies danger.” (laughs)

So I end up moving — constantly — searching for a position where I can stand independently. That’s true for my career, and even for how Tsuribu presents itself. I’m not sure how well I can actually control it, but I’ve always felt that if I don’t stay in a slightly off-center place, I’ll get swept away. Especially now, when the tides are changing so quickly with things like AI, I feel like maintaining that relative positioning is crucial to staying visible.

Aramaki:

Yeah, but thinking only in terms of relative position is dangerous too, right? You end up losing your core — it becomes just a positioning game, which isn’t fulfilling either.

Matsunaga:

Totally. It starts to feel like you’ve lost agency.

Aramaki:

Exactly. It’s hard to balance that. I feel like our stance on positioning might be similar, though.

Matsunaga:

How is it for you personally?

Aramaki:

When I get burned out from making videos, I often start asking myself, “Why am I even doing this?” (laughs) Like, what’s the point of continuing this? Then I think about how people currently perceive me, what they expect from me — and whether just fulfilling those expectations is really the right path. I end up stepping back and asking, “Where does my sense of meaning lie?” I think I do that two or three times a year, just to recalibrate.

That’s part of why I did a lot of independent projects last year — I started feeling like I was becoming “the anime guy.” But my real strength, the reason I was valuable in anime to begin with, was precisely because I came from outside — bringing motion graphics and CG sensibilities into that world. The moment I became too internalized within anime, that uniqueness started fading.

So I thought, I need to step back and reestablish distance. I wanted to rebuild motion-graphics-style expression on my own terms again.

Matsunaga:

Right — to re-center the structure so that your style exists first, and anime becomes one of the contexts that draws from it.

Aramaki:

Exactly. I felt like if I didn’t step away, I’d lose my sense of distance from anime altogether.

Matsunaga:

So in a sense, you’re constantly keeping a bird’s-eye view of your own advantages.

Aramaki:

Maybe. I think anyone who’s properly established ends up doing that to some extent (laughs). If you want to work independently as a designer or director, it’s kind of a required parameter — you have to keep assessing your own position.

Matsunaga:

Otherwise people stop having a reason to ask you specifically, right? You need that “signboard” — something that clearly says, this is my value.

Aramaki:

Yeah, though there are also people and studios that quietly keep making CG work as pure craftsmen, without ever signaling that value.

Matsunaga:

True — but not everyone has that restless “boredom instinct” you have (laughs). I’m the same way. Maybe calling it “otherness” is putting it too nicely, but still.

Aramaki:

Yeah, maybe having people who feel that discomfort — those who can’t help existing slightly outside — is actually important.

Matsunaga:

And being able to recognize that and turn it into something marketable — that’s kind of the trick, right? Otherwise you’re just perpetually frustrated. Around ten years ago, graphic designers were taught to “have a wide range,” and I think that mindset still exists in motion graphics too — that you should be able to do anything. I used to believe in that ideal. But I’ve also realized that by taking on all kinds of work to expand my range, I’ve put up more safety nets — like I’ve lost the ability to do something truly reckless (laughs).

Now, I feel like the industry’s shifting. There are more cases where people hire someone for one specific style, not for versatility. Like a restaurant with only one signature dish, instead of a family restaurant with a huge menu.

Aramaki:

I actually envy that. I really do.

Matsunaga:

Yeah, I sometimes wonder if that’s actually the stronger survival strategy right now — though who knows how long it’ll last (laughs). For me, I just try to keep my form steady — not make it too flexible.

Aramaki:

I’m more on the “do everything” side, so I admire people with a clear personal style. But at the same time, if I were in that position, I think I’d be terrified — wondering if that strategy would actually hold up long-term.

Matsunaga:

Yeah, it’s basically gambling (laughs). If it hits, you survive — if it doesn’t, you die right there.

Aramaki:

I was actually talking with Hiraoka-san the other day. You know how his style of animation is completely one of a kind — totally in a league of its own? Even he was saying, now that AI has come along, “What the hell am I supposed to do with this?” (laughs).

It really surprised me — that someone with that level of artistic strength could feel that way.

Personally, I’ve kind of given up on the idea of expressing individuality purely through technique or style. Instead, I’m leaning into this contrarian attitude — trying to find interesting interpretations and approaches to things. That’s the only way I can keep going, I think. Even with AI coming into the picture, I still feel like maybe, just maybe, there’s a way to survive through that kind of methodology — by staying clever about how you interpret and twist things.

Matsunaga:

Yeah, I also tend to think in terms of “what AI probably wouldn’t do.” I guess that’s just a result of constantly thinking about positioning. When a big shift happens, I can kind of immediately go, “Okay, then maybe I should go in the opposite direction.” It’s the same with social media — when everyone starts doing the same thing, doing something different naturally makes you stand out. So in that sense, always being aware of your position might actually make it easier to adapt.

Aramaki:

Right. And as long as you can stand out through the content itself, I think that’s still a good place to be.

The other day, I was listening to a podcast by the book critic Kaho Miyake, and she was saying that nowadays, if you’re an author, it’s no longer enough to just write books — you have to turn yourself into a kind of talent. Like, self-promotion has become essential.

Matsunaga:

Right, like the oshi-katsu mindset — people support the person because it’s them writing, not just because of the work itself.

Aramaki:

Exactly. She said, “If you want your books to sell, you basically have to become your own Dentsu.” (laughs)

Of course, with filmmaking and motion work being mostly client-based, maybe we don’t need to go that far. But still — if every industry eventually reaches the point where everyone has to become a YouTuber to survive, that’s going to be rough for people like us.

A lot of us see ourselves as craftspeople, so the idea that personal branding becomes a prerequisite to staying alive — that’s a pretty painful future to imagine.

Matsunaga:

Yeah. The beauty of this world used to be that your work could speak for you.

Aramaki:

Exactly — but if it becomes all about who’s the most entertaining personality, then Kansai people are gonna dominate (laughs). If humor and charisma become currency, it’s their game.

Matsunaga:

(laughs) So in the end, it’s like — do we all need to have “nin” now? That personal flavor, that comic instinct?

Aramaki:

Yeah, maybe it’s inevitable as part of the times. But it’s definitely not the kind of future I’m hoping for.

Though I bet Kansai folks are out there saying, “Our time has come!” (laughs)

Matsunaga:

Oh, absolutely. They’re probably already saying, “Kansai is hot right now!” (laughs)

In the full episode, we dive even deeper — exploring the similarities and differences between the two, the contrasts in sensibility between Kansai and Kanto, and how each of them analyzes the roots of their sense of color and form. Aramaki also shares rare behind-the-scenes stories about his work on Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time and his experience collaborating with Studio Khara.

The first session turned out to be a rich and thought-provoking conversation centered on the themes of “externality” and “distance.” Be sure to give it a listen.

Thank you so much, Aramaki-san! (We ended up talking for almost three hours!)