In January 2026, I.CEBERG participated in the TOKYO PROTOTYPE exhibition.

This series of articles introduces the works created by each MAISON.

For more details about the event, please visit here.

Work Overview : Bio Remix

Bio Remix is an an attempt to re-edit the patterns and markings found in living organisms as fashion.

By exploring biological processes such as growth, differentiation, and repetition, the work dissects and expands a fetishistic fascination with natural phenomena through their transition into clothing.

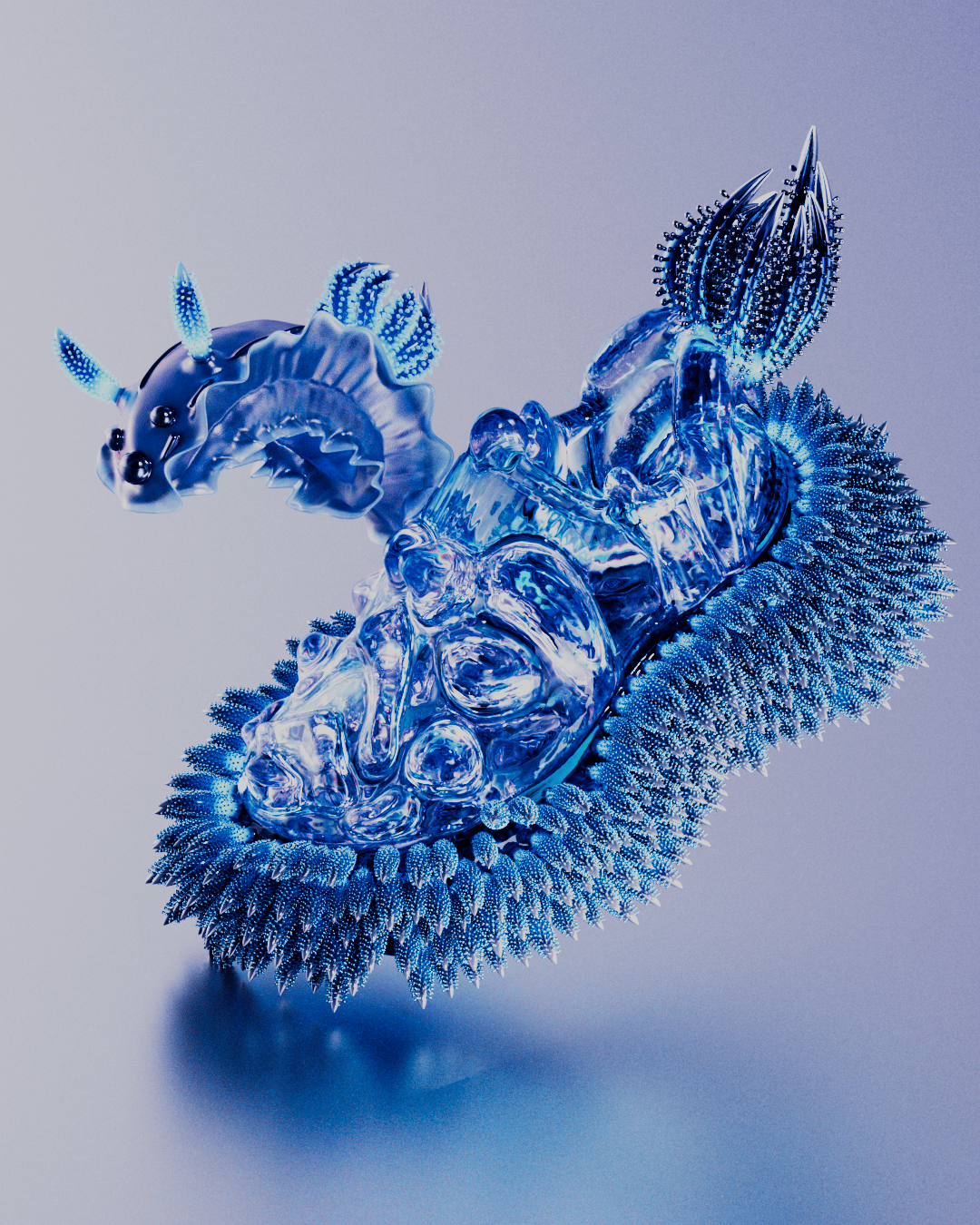

For this exhibition, the focus is on sea slugs (nudibranchs), marine organisms with primitive forms yet an extraordinary diversity of pattern variation.

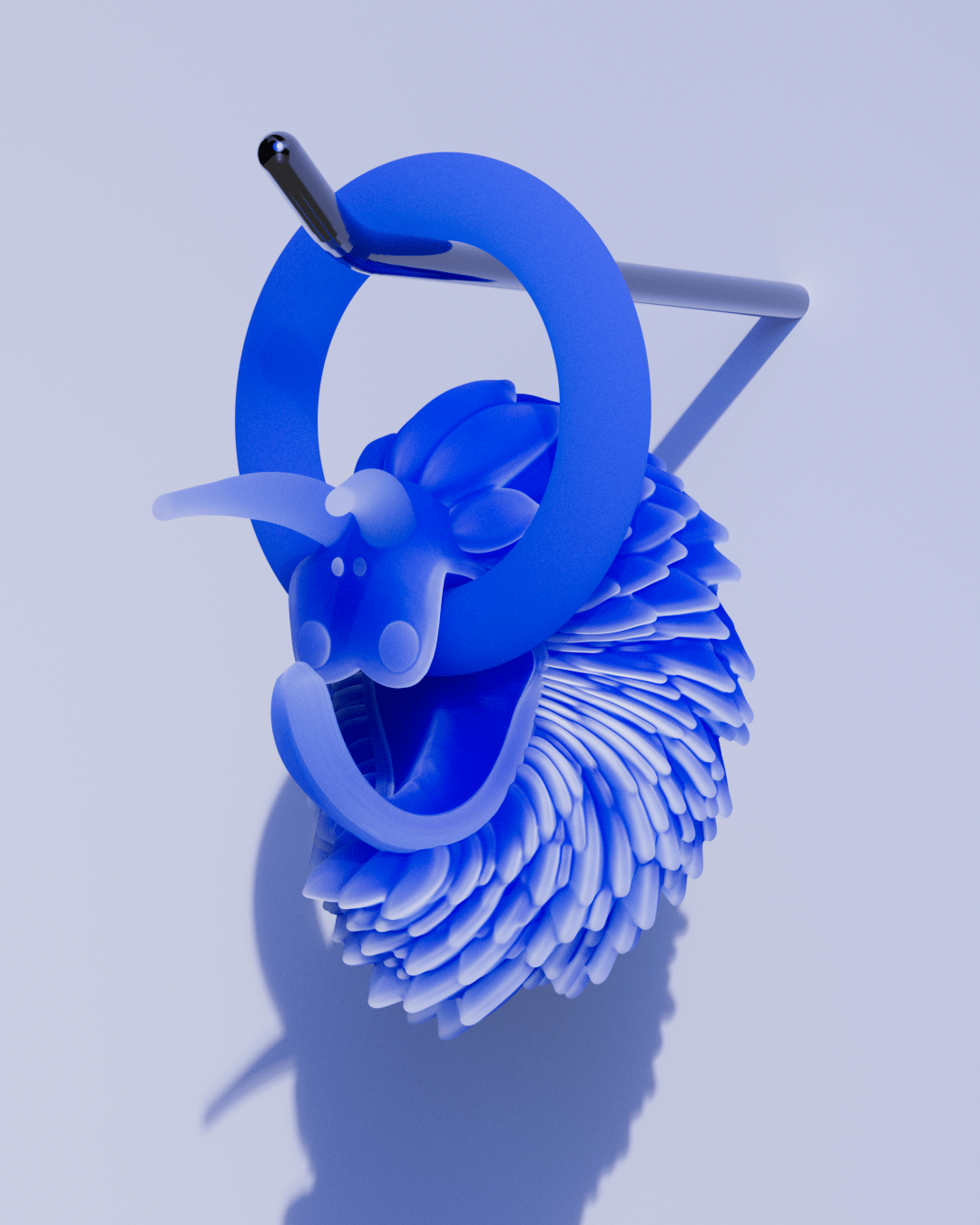

Model: Chromodoris willani

Model: Doriprismatica atromarginata

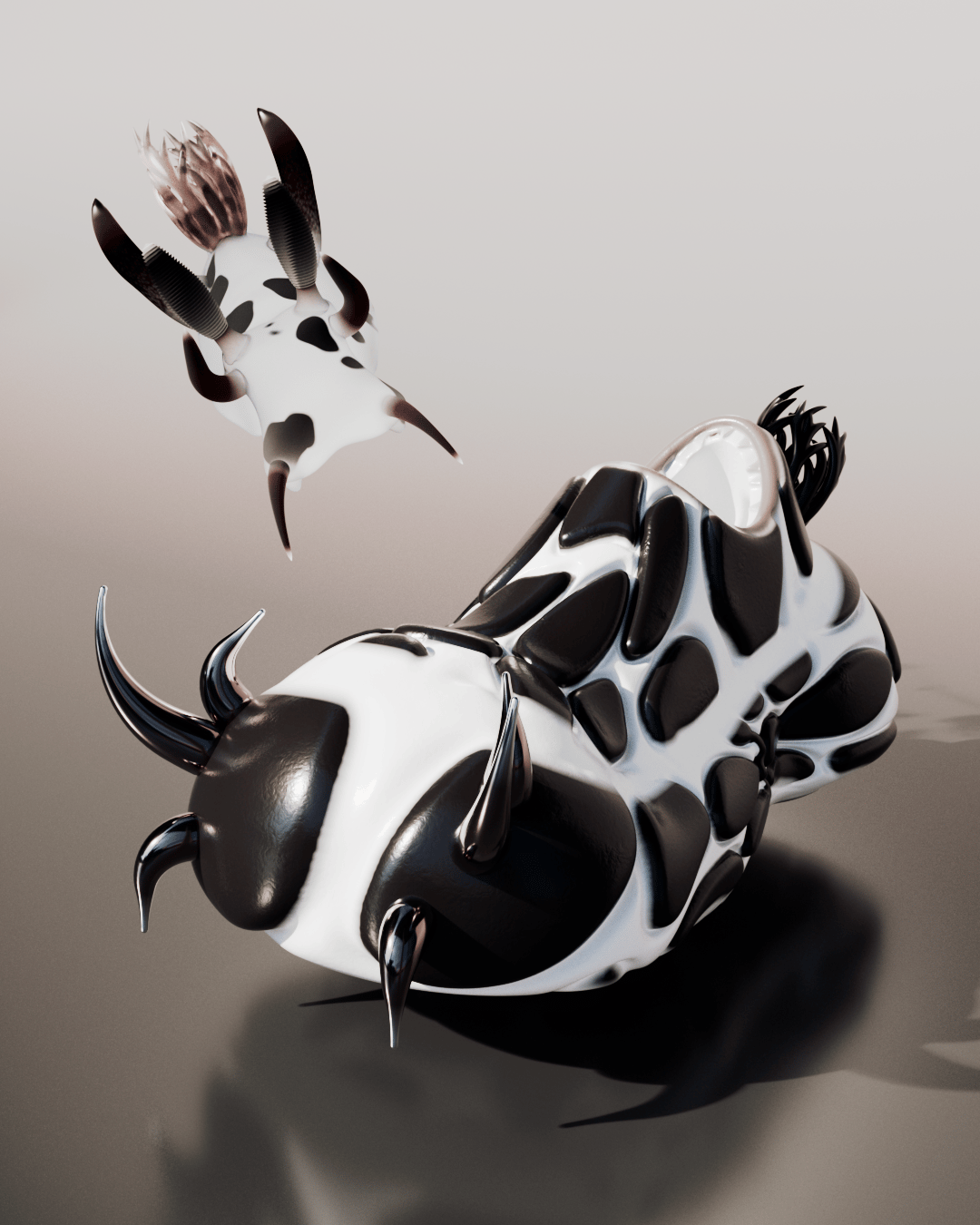

Model: Sakuraeolis sakuracea

Model: Trapania naeva

Model: Thecacera pacifica

Rather than directly transcribing the visible, surface-level structures of living organisms, every stage of this work—from modeling and texturing to animation—reconsiders the spatiotemporal rules and constraints that give rise to those structures.

The entire system is constructed parametrically, allowing form to emerge from underlying logic rather than imitation.

Deliberately dismantling and reconstructing forms that already appear complete is an indirect and time-consuming process.

However, this approach feels like a natural consequence of a fundamental impulse: a desire to understand more deeply what is perceived as beautiful, and what instinctively draws the eye and the mind.

Through this process, a personal visual language and way of seeing gradually begins to take shape.

It is precisely in the moments where the work departs from the original biological forms that new discoveries emerge—revealing possibilities beyond their source.

This work represents a cross-section of my practice, capturing the constant movement between logic and surface, structure and appearance.

If viewers are able to sense the freedom and pleasure that arise from remixing and mashing forms beyond species and boundaries—and the quiet joy of encountering unfamiliar forms of life—then the work has fulfilled its intent.

Unfolding Nature Through Making

Why nudibranchs, and why living organisms at all—this line of inquiry is rooted in a long-standing fascination with understanding the natural world through structure and logic.

Since my student years, I have been drawn to theoretical physics, frequently reading texts on fluid dynamics, quantum mechanics, condensed matter physics, and astrophysics.

I was deeply attracted to the elegance with which simple equations written on a page could describe the overwhelming complexity of reality.

As my curiosity gradually moved toward increasingly complex systems, it eventually converged on the phenomenon of life itself.

Reading What Is Life? by Erwin Schrödinger was a formative experience—it was both inspiring and unsettling.

While the book revealed the possibility of approaching life through physical principles, it also made clear how difficult it is to fully account for the immense diversity and complexity of living systems through mechanics alone.

Subsequently, encounters with Jakob von Uexküll’s A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans and texts on mathematical biology shifted my perspective.

Through these readings, my interests began to connect with embodied informatics and media art, leading me to consider nature and life from a more external, observational standpoint—one mediated by systems, perception, and representation.

Today, through visual expression at I.CEBERG, I continue to excavate this curiosity—unfolding nature not by explaining it outright, but by constructing processes through which it can be sensed, reinterpreted, and rediscovered.

In the end, I sometimes catch myself thinking that my trajectory has drifted toward something far more casual than expected.

Yet, with a slight sense of hesitation, I have come to accept that my interest may no longer lie in solving beauty through theory, but rather in discovering ways of feeling beauty more deeply.

For me, the pleasure of making has always been inseparable from the pleasure of knowing.

To create, I must observe form and texture closely.

And within the parametric and procedural methods I work with, each form demands an understanding of the processes and logics through which it emerges—requiring repeated cycles of research, speculation, and reconstruction.

Through the act of making, my resolution toward the subject gradually sharpens, and with it, my affection deepens.

This intertwining of intellectual inquiry and a quiet love letter to the motif itself is embedded at the core of my practice.

Encountering Nudibranchs / Making the Work

My encounter with nudibranchs was surprisingly recent—I discovered them in early December 2025, just two months before the exhibition.

By my own admission, it was a rather impulsive, almost naïve discovery.

While researching ideas around fish and ornamentation, I happened upon nudibranchs by chance, and quickly became captivated by their charm and extraordinary diversity of forms and colors.

Because of how sudden this encounter was, there was initially no plan to make a work centered on nudibranchs.

However, a series of circumstances—including the accidental loss of past data while modifying my computer—forced a reassessment of direction.

There were various temporary solutions available, but none felt particularly compelling. Instead, I chose to start from scratch and commit to creating an entirely new work based on nudibranchs.

The decision was made on December 24th—Christmas Eve—with exactly one month remaining before the exhibition.

Process diary — December 24, 2025. The starting point.

Surprisingly, the initial stages progressed almost exactly as I had hoped, and my excitement quickly spiked.

I could feel the results of daily practice—my “Houdini muscles” had clearly been strengthening.

(The real ordeal, of course, was still yet to come.)

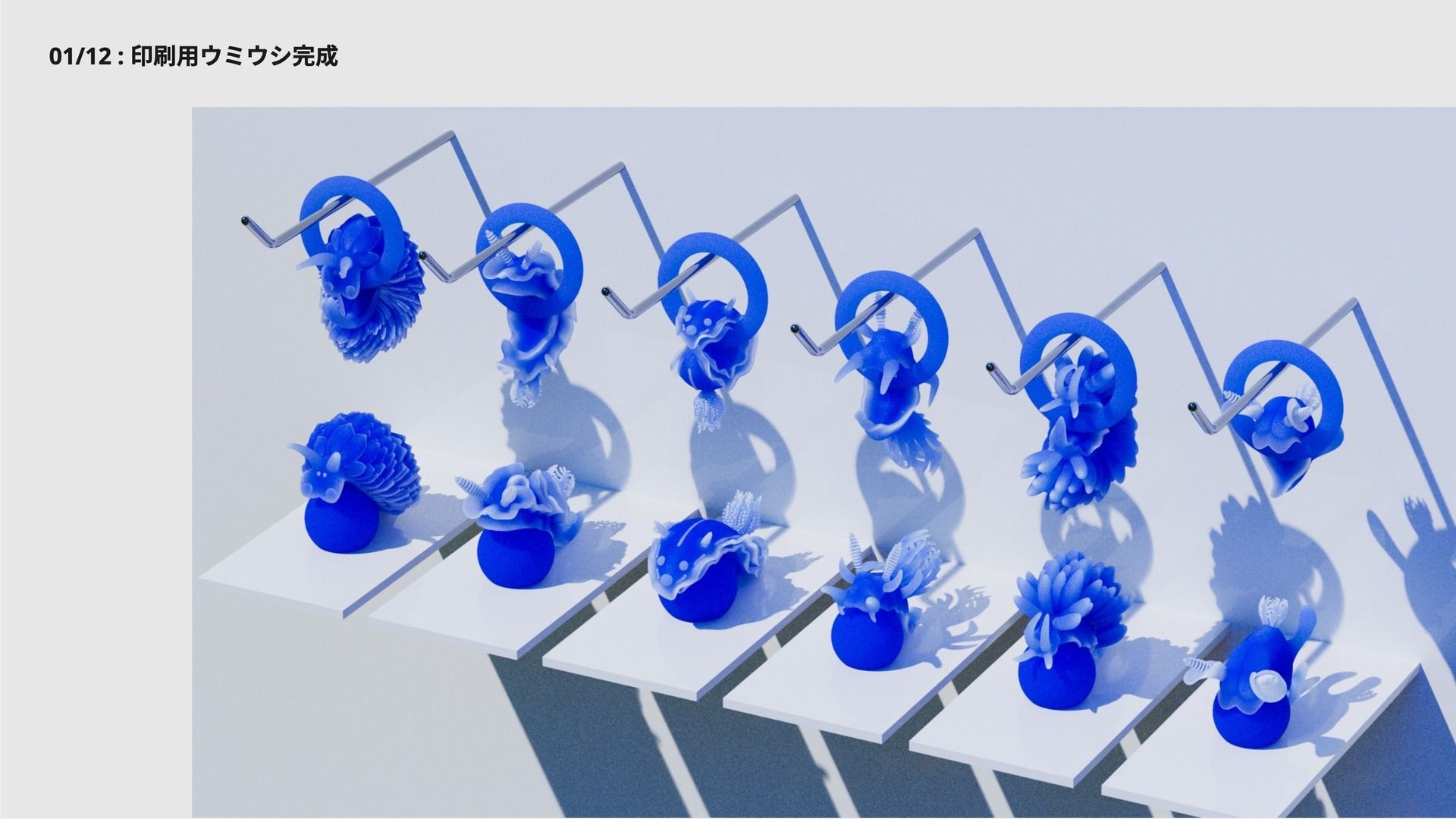

After numerous experiments and adjustments, the nudibranch model for 3D printing—intended for sale as merchandise—was finally completed.

January 12th. With the year-end holidays having slipped by, I suddenly found myself with just over two weeks remaining before the exhibition.

There had always been a plan to use two displays for the video installation, but the list of tasks was still overwhelming: optimizing models for animation, refining materials, developing motion.

And not a single shoe had been completed yet.

From the outside, the situation looked dire.

Yet, somewhat unexpectedly, I didn’t feel much panic—at least not until the final three days.

Part of this calm came from a strange confidence that I could already see the entire sequence of steps leading to completion within my own plan.

More importantly, the process of discovering something unknown while simultaneously giving it form was simply, and genuinely, enjoyable.

It’s also possible that the situation had become so critical that I had looped past anxiety and into a kind of enlightenment.

Still, I believe this numb, suspended state is sometimes necessary—to avoid unnecessary mental collapse or the trap of overthinking.

Since the opportunity presented itself, I’ve included excerpts from the diary I kept during this period.

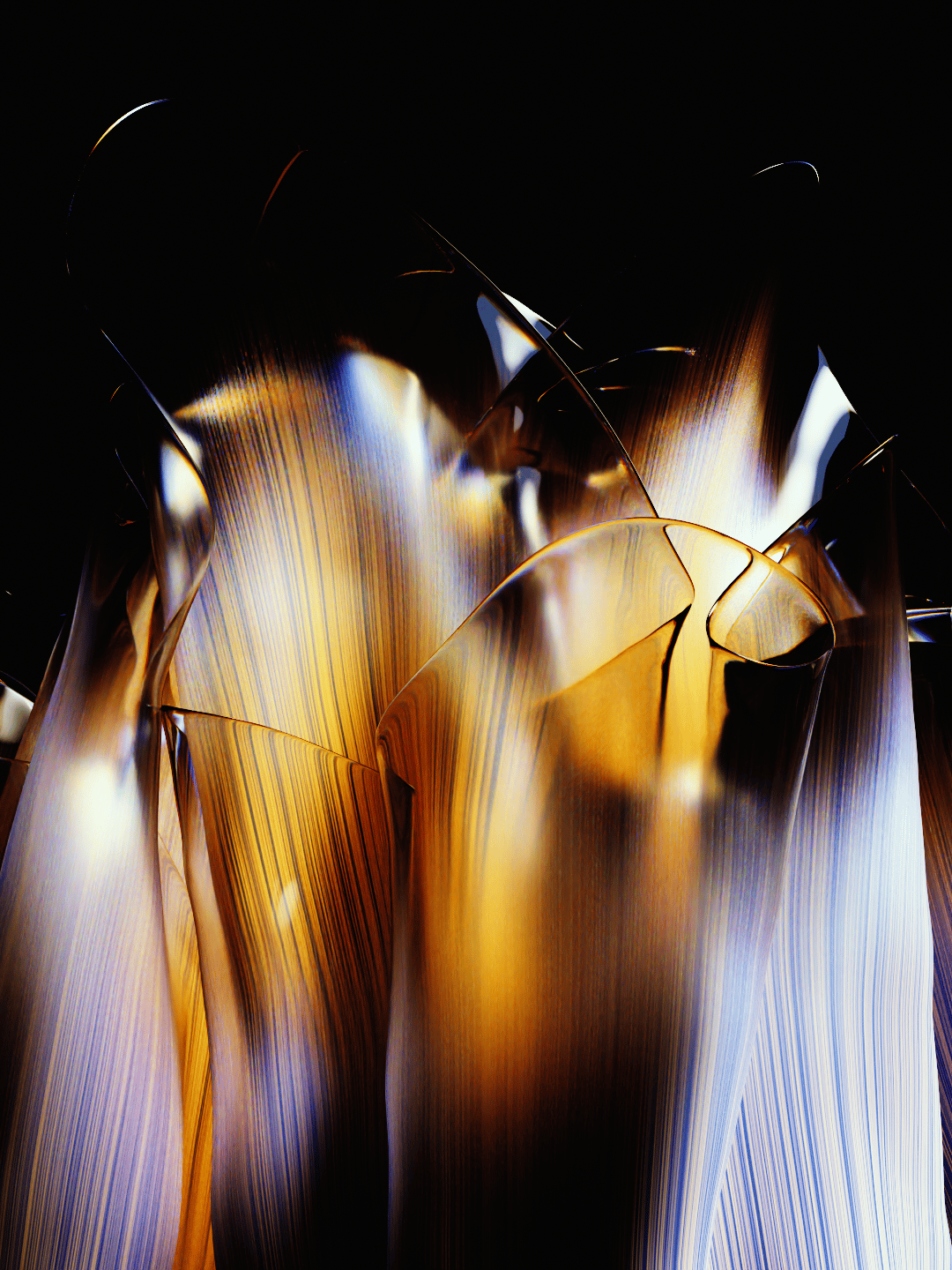

Process diary — January 14, 2026. When things get hard, start with glass to lift the mood.

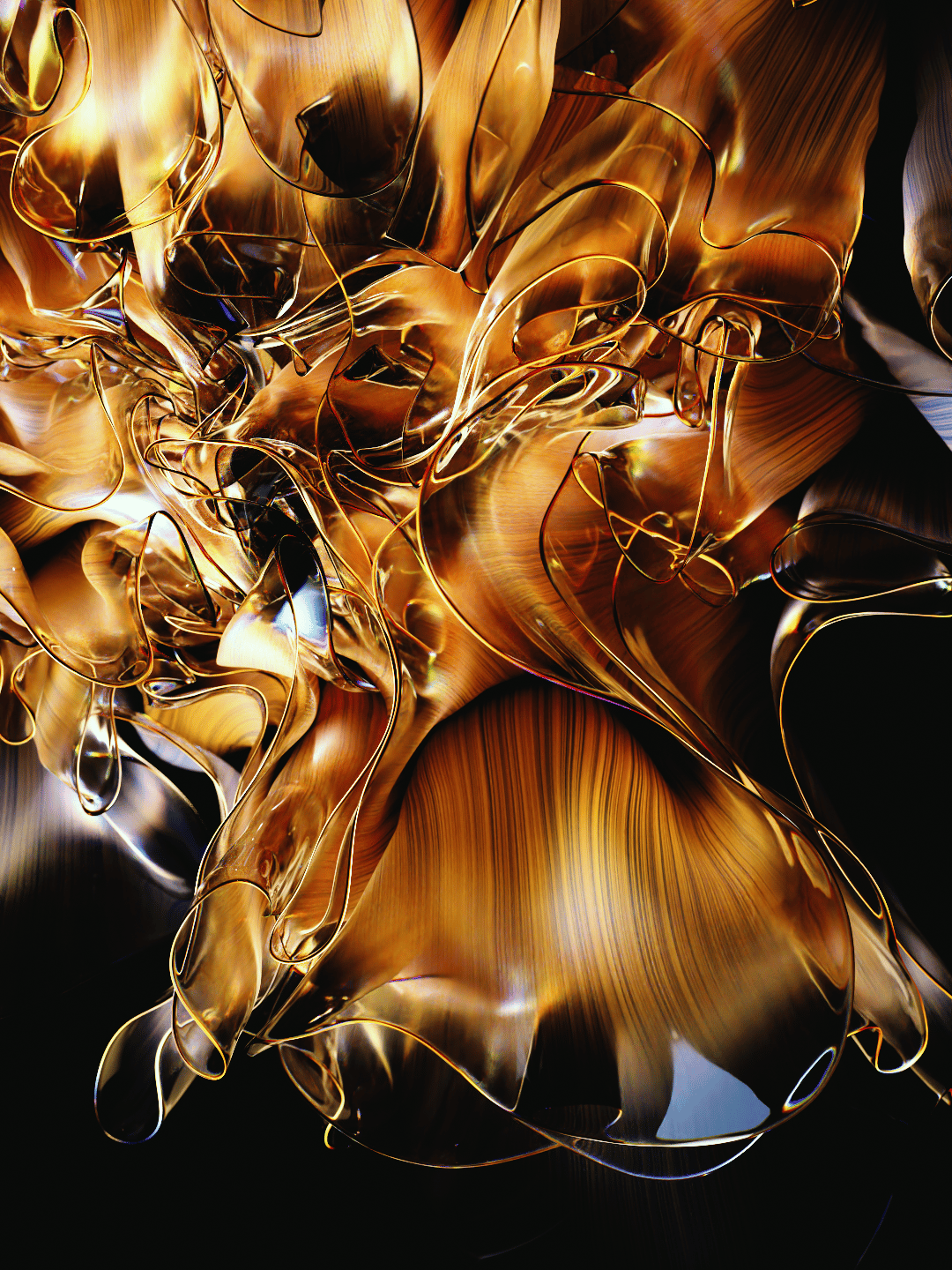

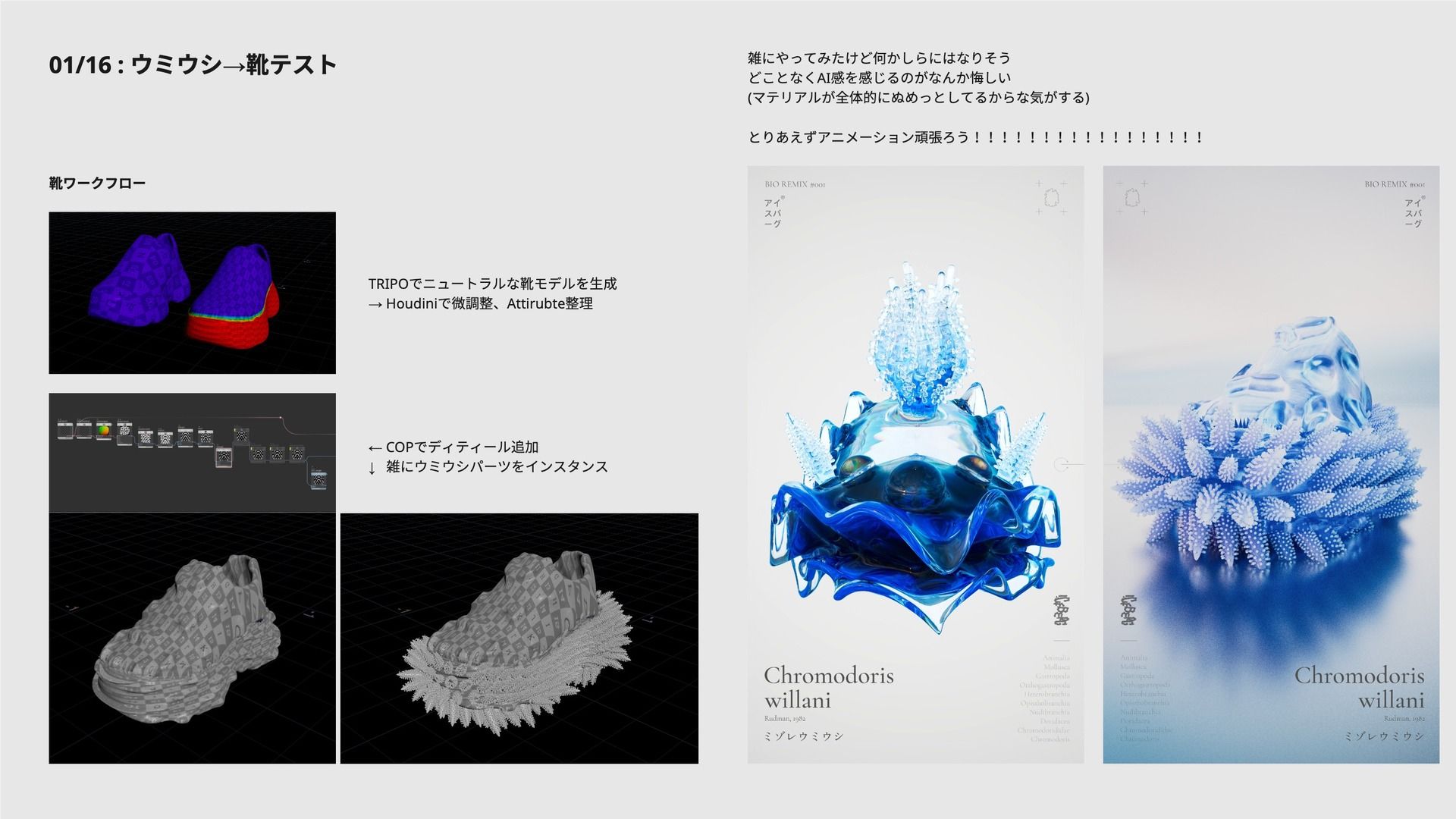

Process diary — January 16, 2026. Shoes looked intimidating, so I boosted the mood with volume, glass, and graphics.

Process diary — January 22, 2026. Models and materials finally came together. (One quietly dropped out.)

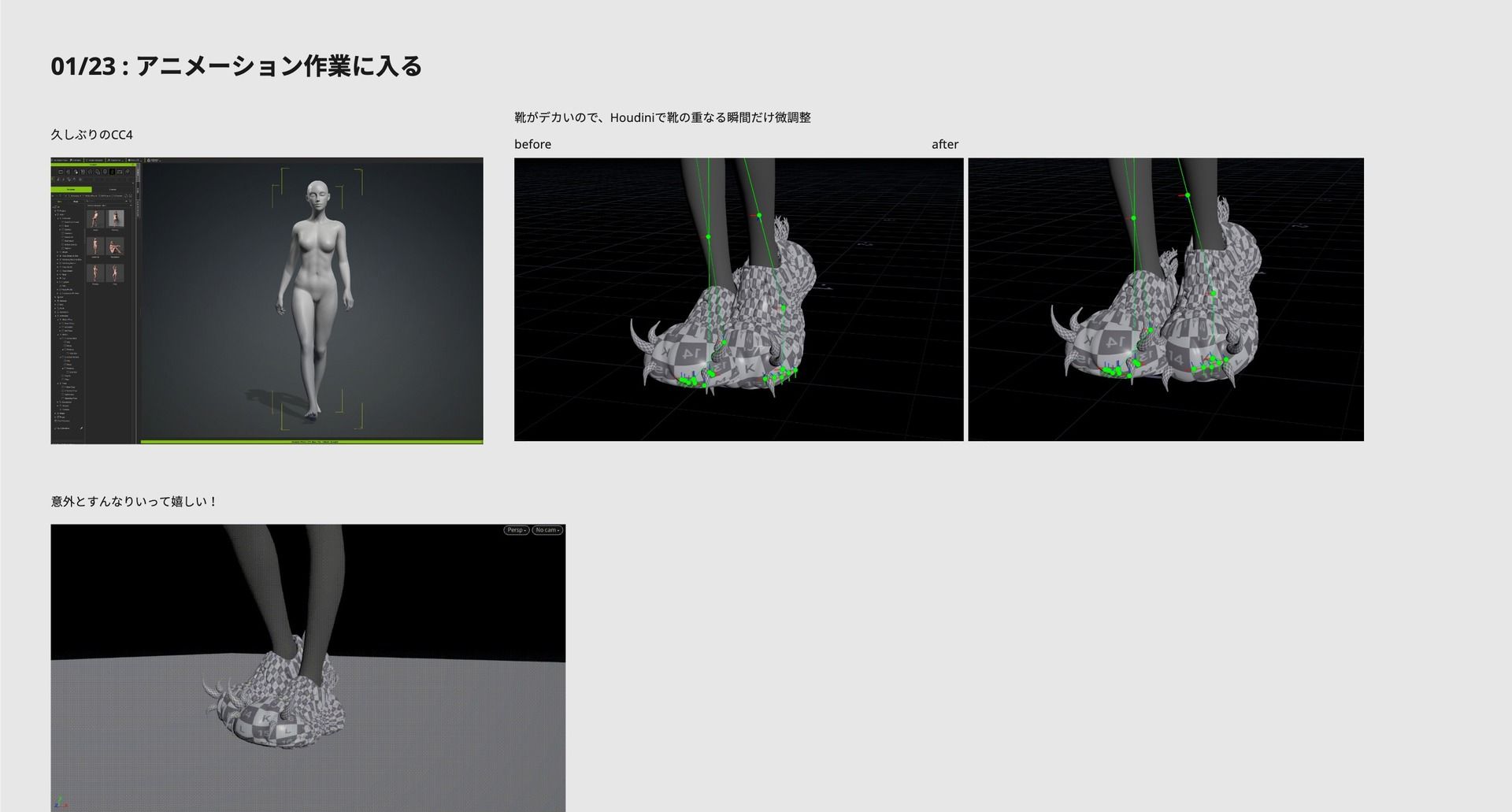

Process diary — January 23, 2026. Base animation from CC4, refined in Houdini.

The record ends on January 23rd.

…

Learning Ornament from Nature

Why translate living organisms and natural phenomena into fashion and ornamentation?

First, simply because I love clothing.

I do buy a lot of clothes in my private life, but beyond that, fashion operates on multiple levels: it is a form of spatial composition around the body, a visual expression of inner preferences, and a field shaped by the complex movements of soft materials such as fabric. These layered qualities make it endlessly compelling.

Non-human organisms, too, possess forms of ornamentation—developed through diverse survival strategies such as protection from predators, adaptation to environments, courtship, movement, and the capture of prey.

When viewed as ornament born from radically different bodies and conditions of existence, these forms invite translation. It feels almost inevitable to want to bring such non-human ornamentation into the realm of human dress.

A friend of mine once said, “Nature is our teacher.”

I couldn’t agree more.

However, despite several attempts so far, many of these explorations remained at the level of concept.

I came to realize that in order to truly construct pieces that can be worn and inhabited, it is necessary to first learn from existing forms and conventions—only then introducing experimental deviations from within those frameworks.

For this exhibition, I decided to make the sources of natural reference more specific.

At the same time, I began to consider a reversal of direction: instead of translating nature into ornament, I explored the idea of ornamenting living organisms with artificial decoration.

The initial concept was to create “a gyaru adorned with snake scales” and “a snake adorned as a gyaru.”

The decision to use two displays in the exhibition space was originally made to present this contrast—placing a “creature-like gyaru” and a “gyaru-like creature” face to face.

Around the time I began experimenting with the snake concept, a series of practical circumstances—including data loss, decisions around merchandise, and scheduling constraints—gradually redirected the project toward creating nudibranchs.

Because of this trajectory, my exploration of ornamentation as a means of moving between humans and nature is still very much in its early stages.

This inquiry is not limited to nudibranchs and will continue to evolve through future works.

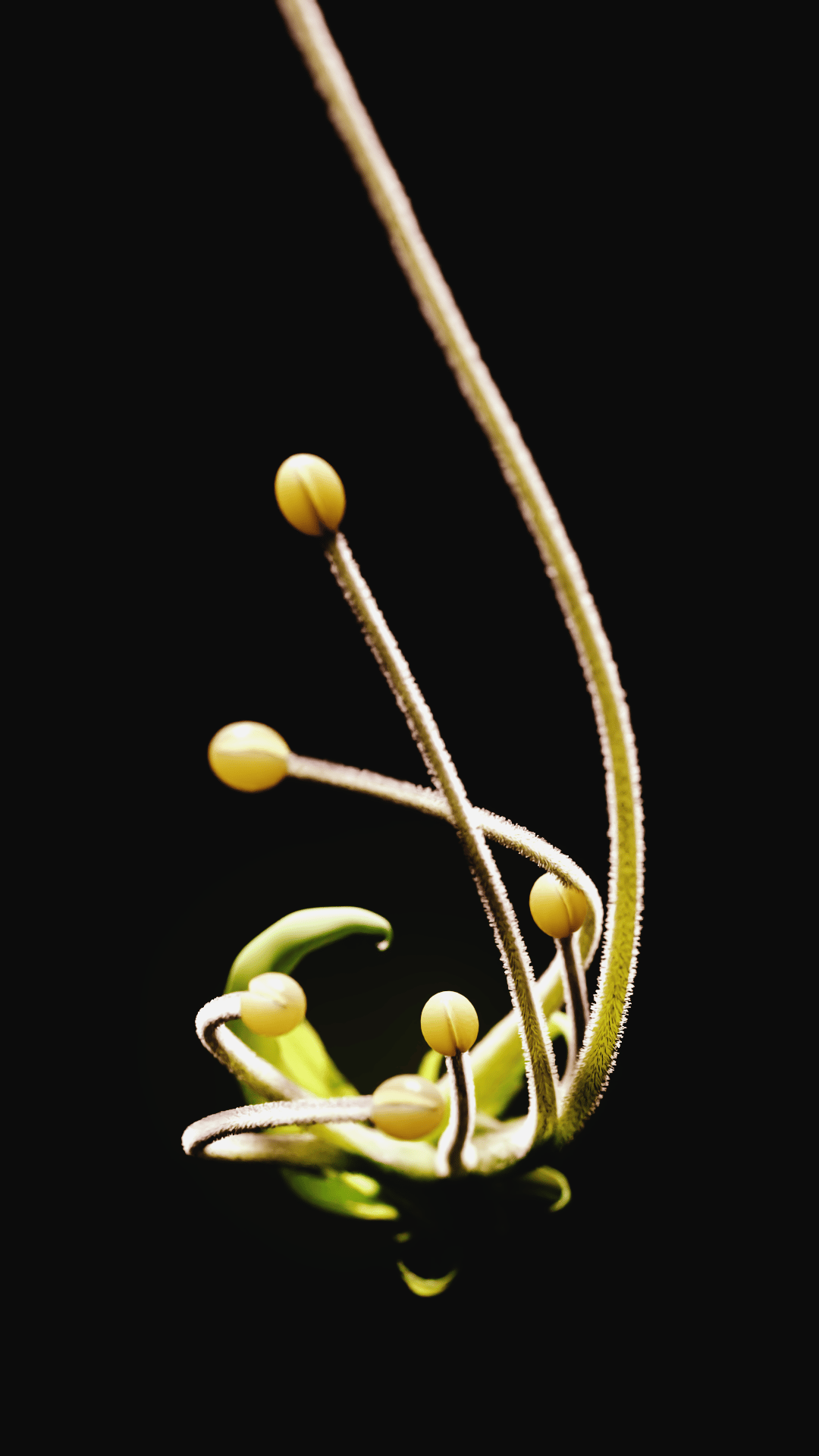

The graphics leaned toward a field-guide vibe—might be worth turning this into a book.

I hope you’ll look forward to what comes next.

aside

One nudibranch did not make it into the final video work due to scheduling constraints.

Its name is Hoho-beni-moumiushi—a species that appears to be born with a natural blush on its cheeks, unapologetically cute and slightly calculating.

Taxonomically, it is in fact an undescribed species and has yet to be given an official scientific name.

For now, it is recorded as Costasiella sp., meaning “some member of the genus Costasiella”—a placeholder that quietly admits, we don’t quite know what this is yet.

Let’s hope it continues to thrive on its innate charm, and patiently wait for the day it is formally described and welcomed into the taxonomic record.